Saltz on the Death of the Gallery Show

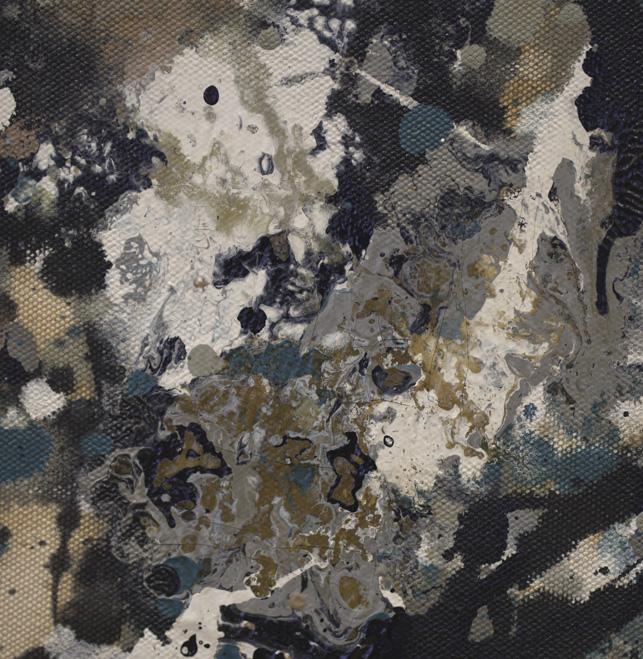

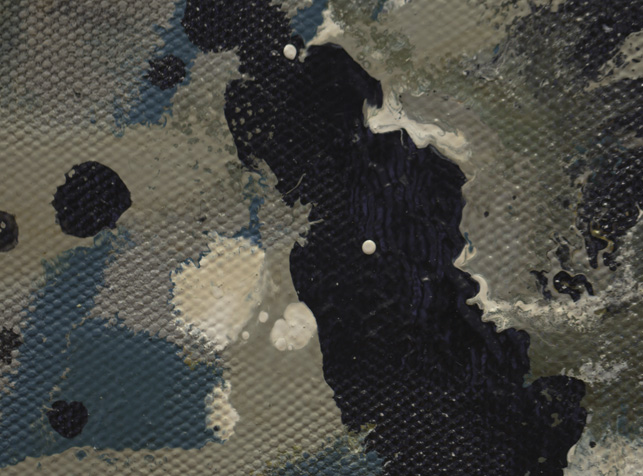

Keith Haring at Tony Shafrazi Gallery, 1982.

Keith Haring at Tony Shafrazi Gallery, 1982.

Gallery shows: light of my life, fire of my

eyes. I love and long for them. I see maybe 30 a week, every week of the

year. Much of what I know about contemporary art I learned from hanging

around artists and from going to galleries. Bad shows teach me as much

as good ones. A great thing about galleries—especially for someone who

spends most of his time alone at a computer, typing—is that they’re

social spaces, collective séances, campfires where anyone can gather.

I’m a blabbermouth, so in galleries I turn to strangers and blurt

whatever I’m thinking about whatever we’re looking at. If they don’t

think I’m a creepy geezer, they’ll tell me what they’re thinking, too.

Then I see whole new things. As disembodied as they can be, galleries

are places where one can commune with the group mind. We have more of

them than any other city does, and admission is free.

The clustering of hundreds of galleries in several neighborhoods

has meant that a huge swath of the art world is continually being

presented at our doorstep. That is changing, and changing fast. These

days, the art world is large and spread out, happening everywhere at

once. A shrinking fraction of galleries’ business is done when

collectors come to a show. Selling happens year-round, at art fairs,

auctions, biennials, and big exhibitions, as well as online via JPEG

files and even via collector apps. Gallery shows are now just another

cog in the global wheel. Many dealers admit that some of their

collectors never set foot in their actual physical spaces.

The beloved linchpin of my viewing life is playing a diminished

role in the life of art. And I fear that my knowledge of art—and along

with it the self-knowledge that comes from looking at art—is shrinking.

Artists and dealers are as passionate as ever about creating good

shows, but fewer and fewer people are actually seeing them. Chelsea

galleries used to hum with activity; now they’re often eerily empty.

Sometimes I’m nearly alone. Even on some weekends, galleries are quiet,

and that’s never been true in my 30 years here. (There are exceptions,

such as Gagosian’s current blockbuster Basquiat survey.) Fewer ideas are

being exchanged, fewer aesthetic arguments initiated. I can’t turn to

the woman next to me and ask what she thinks, because there’s nobody

there.

Instead, the blood sport of taste is playing out in circles of

hedge-fund billionaires and professional curators, many of whom claim to

be anti-market. There used to be shared story lines of contemporary

art: the way artists developed, exchanged ideas, caromed off each

other’s work, engaged with their critics. Now no one knows the

narrative; the thread has been lost. Shows go up but don’t seem to have

consequences, other than sales or no sales. Nothing builds off much

else. Art can’t get traction. A jadedness appears in people who aren’t

jaded. Artists enjoying global-market success avoid showing in New York

for fear any critical response will interfere with sales. (As if iffy

international art stars could have their juggernauts stalled by a measly

bad review or two. A critic can only dream.) Ask any artist: They’re

all starting to wonder what’s going on.

I don’t even mind so much that the role of the critic is

diminishing. Clement Greenberg was a bully, anyway. Primacy always

belongs to art and the artist. I’ve tried to keep overhyped careers in

check, and had no effect whatsoever. In fact, so many shows in so many

places mean that we now have an overload of writing about art. Joseph

Beuys said, “Everyone is an artist.” Now everyone actually is a writer.

Like exhibitions that can’t get traction, commentary also has a hard

time gaining a foothold, unless you yourself enter the arena of

spectacle, becoming something of a spectacle yourself. (Believe me; I

know.) Adding to this, a generation of academically trained critics were

taught to believe they should write in impenetrable language and

refrain from opinion and negative criticism.

This is not to say that art is not selling. Websites for high-end

sales and auctions are burgeoning. We read of sites with technology

that allows collectors “to visualize artwork in 3-D space without ever

leaving your desk,” an “animated gif display,” an “online sales

platform,” “sortable JPEG images.” We hear of an “online collector

profile and gallery … to list your preferences and to view our art

selections tailored to you.”

When so much art is sold online or at art fairs, it’s great for

the lucky artists who make money, but it leaves out everyone else who

isn’t already a brand. This art exists only as commerce, not as

conversation or discourse. Art dealer Kenny Schachter has noted that

“the higher and higher prices are for fewer and fewer artists.”

Those sales platforms are proliferating, too. Paddle8 advertises

that it provides two types of online auctions. Another, called Artspace,

recently raised $8.5 million in expansion capital, including money from

the Russian collector Maria Baibakova, who also owns a “platform for

cultural production.” Still another site, Artsy—co-founded by Dasha

Zhukova, partner of billionaire Russian collector Roman Abramovich—says

it will “make all the world’s art accessible to anyone with an Internet

connection.” The CEO tells us, “The more you use Artsy the more we learn

about what you like. Over time, we can better suggest things for sale

that you might like. Even if there are no works by an artist for sale

today … in the future, if the work becomes available, we’ll notify you.”

The auction houses are in on the new game as well. Christie’s, in

partnership with a company called Y&S, now provides “a venue for

emerging artists not yet represented by galleries” and “creates a bridge

between young artists and a young audience.” Translation: “We’re

cutting out dealers. Come on down. Make a killing.” Thus, unrepresented

artists go straight to auction. Work that is sold this way exists only

in collector circles. No other artist gets to see it, engage with it,

think about it. The public functions of the gallery space and its

proprietors—curation, juxtaposition, development—are bypassed and

eliminated. All these people supposedly want to help artists, and they

probably think they are doing so. But they’re engaged in something else,

and it makes being around art less special. Too many of the buyers keep

their purchases in storage, in crates, awaiting resale. Mediocre

Chinese photorealism has become a tradeable packaged good.

I’ll admit that there’s something democratizing about all this.

All those buyers can judge for themselves what they like and put their

bank vaults where their taste is. The paradox is that art is not

inherently democratic. It’s a kind of meritocracy—albeit with the

interior high-school rules of some other nebula. Today, those with the

most money are the only ones whose votes count. Although I love that

young broke artists who can’t travel to New York or Berlin can look at

art online, think about what it means, and use this information in their

own work, seeing art in the flesh really gives you something unique. I

have only once gone underground to see cave paintings. But that one cave

made an enormous difference in my life.

So far, thank goodness, the galleries themselves

are not disappearing, but that day may be coming. Owing in part to the

Chelsea condo-and-office boom, even the successful ones are fighting for

their financial lives. The excellent Postmasters Gallery just saw its

West 19th Street rent raised to $30,000 a month and will have to move.

Other mid-level Chelsea dealers are being priced out as well. Longtime

gallerist Casey Kaplan told Bloomberg News, “You won’t find much

experimentation if the rents continue to escalate …those kinds of

galleries won’t be here.” Postmasters’ owner, Magda Sawon, has explained

that “mid-range galleries are going to just vanish from Chelsea,”

adding, “the whole middle is basically pulverized.” Even if they

survive, I wonder whether a much bigger shakeout is about to happen, one

that makes art resemble any mainstream business—just another culture

industry that’s eaten itself alive.

Or whether it’s about to go supernova. The galleries that are

best suited to this new world are the massive multinationals, whether

for reasons of territoriality, market share, or dick waving. I love big

galleries as much as I do small ones, but I often wonder if these jumbo

spaces aren’t often aesthetic elephant graveyards—places where ambitious

artists and the movements of the sixties and seventies go to die. Many

feel impersonal, and the art can look lost in them. David Zwirner’s new

building on 20th Street adds 30,000 square feet to his space. (I still

can’t figure out why part of his new floor is shiny travertine.) The

multinational Hauser & Wirth just added what looks like a blimp

hangar on West 18th Street. Last I heard, Larry Gagosian, the biggest

elephant of all, has eleven spaces around the world. Perhaps the others

are all supersizing themselves just to compete with Larry. Or maybe they

want to inherit artists from older established galleries like Gladstone

and Marian Goodman. But shouldn’t these dealers be looking for young

talent rather than vying to show Lawrence Weiner and Shirin Neshat?

Maybe everyone will all eventually share Richter and Prince, who will

just relocate every five years.

Bigness isn’t inherently bad. The dealer Gavin Brown has said

that giant art is suited to our age: “When we are able to fly around the

globe in 24 hours, and that is a common occurrence … these large-scale

works might be an unconscious attempt to rediscover awe.” I agree. But

bigness raises prices, and big galleries encourage it. That’s not about

awe; it’s about money. The shows themselves should be smaller, too—I see

many exhibitions that would be twice as good at half the size. Even

Rubens would’ve had a hard time filling these supersize spaces, let

alone doing it once every two years. Duchamp said, “I could have made a

hundred thousand readymades in ten years easily. They would have all

been fake … [A]bundant production can only result in mediocrity.” Many

artists are now in “abundant production,” seducing collectors on the

prowl for stuff to fill their oversize atriums. I’m not sure that a lot

of what they’re making is art at all, and if the artists aren’t making

art and the collectors aren’t collectors, the galleries selling this

product to these people aren’t really galleries anymore, either.

Art doesn’t have to be shown in New York to be

validated. That requirement is long gone. Fine. But consider this: At a

Chelsea opening, a good Los Angeles dealer chided me for not going to

art fairs, not seeing art in L.A. and London, and not keeping track of

the activity online. He said I “risked being out of touch with the art

world,” and he was right. It got me down. As recently as four or five

years ago, I could have crowed that because I see so many gallery shows

every week, I know what’s going on. That’s slipping away, if it isn’t

already gone.

I brooded for months over this. Then I started thinking it

through, and instead of focusing on the “being out of touch” part of

what he said, I started thinking about “the art world.” Something

clicked and brightened my mood. There is no “the” art world anymore.

There have always been many art worlds, overlapping, ebbing around and

through one another. Some are seen, others only gleaned, many ignored.

“The” art world has become more of a virtual reality than an actual one,

useful perhaps for conceptualizing in the abstract but otherwise

illusory.

Once we adjust to that, we can work within the new reality. If

the galleries are emptier, the limos gone, the art advisers taking

meetings elsewhere, and the glitz offshore, the audience will have

shrunk to something like it was well before the gigantic expansion of

the art world. When I go to galleries, I now mainly see artists and a

handful of committed diligent critics, collectors, curators, and the

like. In this quiet environment, it may be possible for us to take back

the conversation. Or at least have conversations. While the

ultrarich will do their deals from 40,000 feet, we who are down at

ground level will be engaging with the actual art—maybe not in Chelsea,

where the rents are getting too high, but somewhere. That’s fine with

me.

Looking, making, thinking, experiencing are our starting point.

Art opens worlds, lets us see invisible things, creates new models for

thinking, engages in cryptic rituals in public, invents cosmologies,

explores consciousness, makes mental maps and taxonomies others can see,

and isn’t only something to look at but is something that does things

and sometimes makes the mysterious magic of the world palpable. Proust

wrote, “Narrating events is like introducing people to opera via the

libretto only.” Instead, he said, one should “endeavor to distinguish

between the differing music of each successive day.” That’s what we do

when we look at art, wherever we look at it, however much noise

surrounds it. In galleries we try to discern “differing music,” and it’s

still there right now. I love and long for it.

Five Shows That Changed the Way I See Art

1. Keith Haring at Tony Shafrazi Gallery, 1982. The moment when I understood that all kinds of art could go mainstream. The opening had a “We’ve arrived” vibe.

2. Vito Acconci at Sonnabend Gallery, 1976.

When

I saw Acconci’s table-gangplank-sculpture thing extend out of the

gallery window over West Broadway, I decided to move to New York.

3. Kara Walker at the Drawing Center, 1994.

Vengeance

was nigh in Kara Walker’s giant wall silhouette of slaves and slavers

eating and having sex with one another. It was like the end of Heart of Darkness made flesh: “The horror.”

4. Matthew Barney at Althea Viafora Gallery, 1990.

Seeing one video sculpture by Barney in a large, crappy group show, I thought, Oh my God! This is one of art’s futures. My art-critic wife looked a bit, shrugged, and said, “Boys … It’s pretty male.”

5. Pipilotti Rist at Luhring Augustine, 2000.

Rist’s

trippy video installation cast such a spell on me that I saw the show

nineteen times. I wrote about it but forgot to say I was in love with

it. I also met future art dealer and force-of-nature Michele Maccarone

there.

Note: Readers should keep in mind that I

arrived in New York in 1980, visiting sporadically before that, and

missed many of the formative shows of the seventies. (I was eking out a

living as a long-distance truck driver, then working as a chauffeur for a

rich person well into the nineties.)

*This article originally appeared in the April 8, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.

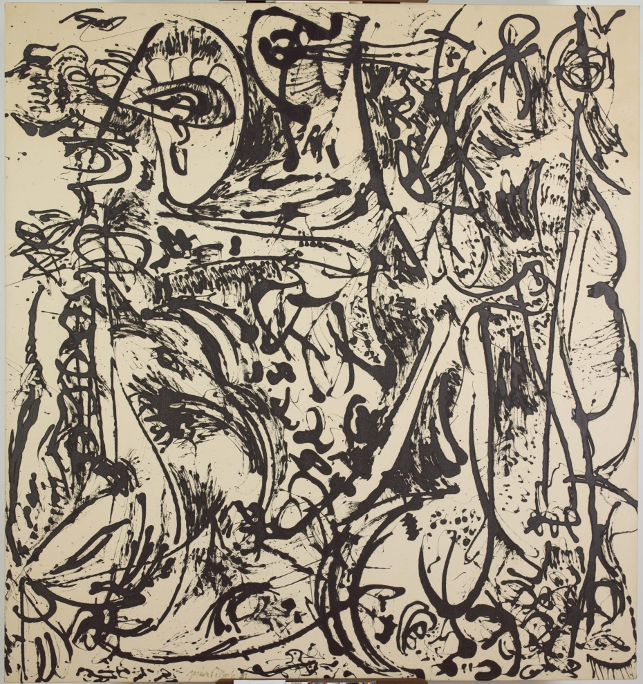

![Pours of black and aluminum paint crisscross an underlayer of thick, white brushwork. An embedded paint cap can be seen just up and to the left of center]](http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/inside_out/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/FFF_detail.sm_.jpg)