COFFERED CEILING

PERMUTATIONS OF THE ARCH

PSEUDOPERIPTERAL

TECHNOLOGY OF "CAEMENTA"

PORTRAITURE

CIVIC,RELIGIOUS,

PRIVATE ARCHITECTURE

VITRUVIUS

FIRST STYLE

SECOND STYLE

THIRD STYLE

FOURTH STYLE

MOSAIC

"AUGUSTAN PEACE"

"DOMUS AUREA"

VESPASIAN AND HIS TIMES

TRAJAN AND HIS TIMES

HADRIAN AND HIS TIMES

ANTONINES ETAL

CONSTANTINE AND HIS TIMES

PANTHEON

INSULA AND URBAN LIFE

LATE STYLES

THE EMERGENCE OF CHRISTIANITY

BASILICAS AND CIVIC SPACE

THE ARCHITECTURAL NEEDS OF THE

"CHRISTIANI"

Archaeologists digging at Pylos, an ancient city on the southwest coast of Greece, have discovered the rich grave of a warrior who was buried at the dawn of European civilization.

He

lies with a yardlong bronze sword and a remarkable collection of gold

rings, precious jewels and beautifully carved seals. Archaeologists

expressed astonishment at the richness of the find and its potential for

shedding light on the emergence of the Mycenaean civilization, the lost

world of Agamemnon, Nestor, Odysseus and other heroes described in the

epics of Homer.

“Probably

not since the 1950s have we found such a rich tomb,” said James C.

Wright, the director of the American School of Classical Studies at

Athens. Seeing the tomb “was a real highlight of my archaeological

career,” said Thomas M. Brogan, the director of the Institute for Aegean

Prehistory Study Center for East Crete, noting that “you can count on

one hand the number of tombs as wealthy as this one.”

The

warrior’s grave belongs to a time and place that give it special

significance. He was buried around 1500 B.C., next to the site on Pylos

on which, many years later, arose the palace of Nestor, a large

administrative center that was destroyed in 1180 B.C., about the same

time as Homer’s Troy. The palace was part of the Mycenaean civilization;

from its ashes, classical Greek culture arose several centuries later. Slide Show

Ancient Treasures From a Warrior’s Grave

CreditDepartment of Classics/University of Cincinnati

The

palaces found at Mycene, Pylos and elsewhere on the Greek mainland have

a common inspiration: All borrowed heavily from the Minoan civilization

that arose on the large island of Crete, southeast of Pylos. The

Minoans were culturally dominant to the Mycenaeans but were later

overrun by them.

How,

then, did Minoan culture pass to the Mycenaeans? The warrior’s grave

may hold many answers. He died before the palaces began to be built, and

his grave is full of artifacts made in Crete. “This is a transformative

moment in the Bronze Age,” Dr. Brogan said.

The

grave, in Dr. Wright’s view, lies “at the date at the heart of the

relationship of the mainland culture to the higher culture of Crete” and

will help scholars understand how the state cultures that developed in

Crete were adopted into what became the Mycenaean palace culture on the

mainland.

Warriors

probably competed for status as stratified societies formed on the

mainland. This developing warrior society liked to show off its power

through high-quality goods, like Cretan seal stones and gold cups —

“lots of bling,” as Dr. Wright put it. “Perhaps we can theorize that

this site was that of a rising chiefdom,” he said.

The grave was discovered this spring, on May 18, by Jack L. Davis and Sharon R. Stocker, a husband-and-wife team at the University of Cincinnati who have been excavating at Pylos for 25 years.

The

top of the warrior’s shaft grave lies at ground level, seemingly so

easy to find that it is quite surprising the tomb lay intact for 35

centuries.

“It

is indeed mind boggling that we were first,” Dr. Davis wrote in an

email. “I’m still shaking my head in disbelief. So many walked over it

so many times, including our own team.”

The

palace at Pylos was first excavated by Carl Blegen, also of the

University of Cincinnati, who on his first day of digging in 1939

discovered a large cache of tablets written in the script known as

Linear B, later deciphered as the earliest written form of Greek.

Whether

or not Blegen’s luck was on their mind, Dr. Davis and Dr. Stocker

started this season to excavate outside the palace in hope of hitting

the dwellings that may have surrounded it and learning how ordinary

citizens lived. On their first day of digging, they struck two walls at

right angles. First they assumed the structure was a house, then a room,

and finally a grave.

“I

was very pessimistic about this,” Dr. Davis said, thinking that the

grave was probably some medieval construction, or that even if it was

prehistoric it would almost certainly have been robbed. But a few days

later, he received a text message from the supervising archaeologist

saying, “I hit bronze.”

What

he and Dr. Stocker had stumbled on was a very rare shaft grave, 5 feet

deep, 4 feet wide and 8 long. Remarkably, the burial was intact apart

from a one-ton stone, probably once the lid of the grave, which had

fallen in and crushed the wooden coffin beneath.

The

coffin has long since decayed, but still remaining are the bones of a

man about 30 to 35 years old and lying on his back. Placed to his left

were weapons, including a long bronze sword with an ivory hilt clad in

gold and a gold-hilted dagger. On his right side were four gold rings

with fine Minoan carvings and some 50 Minoan seal stones carved with

imagery of goddesses and bull jumpers. “I was just stunned by the

quality of the carving,” Dr. Wright said, noting that the objects “must

have come out of the best workshops of the palaces of Crete.”

An

ivory plaque carved with a griffin, a mythical animal that protected

goddesses and kings, lay between the warrior’s legs. The grave contained

gold, silver and bronze cups.

The

warrior seems to have been something of a dandy. Among the objects

accompanying him to the netherworld were a bronze mirror with an ivory

handle and six ivory combs.

Because

of the griffins depicted in the grave, Dr. Davis and Dr. Stocker refer

to the man informally as the “griffin warrior.” He was certainly a

prominent leader in his community, they say, maybe the pre-eminent one.

The palace at Pylos had a king or “wanax,” a title mentioned in the

Linear B tablets, but it’s not known if this position existed in the

griffin warrior’s society.

Ancient

Greek graves can be dated by their pottery, but the griffin warrior’s

grave had none: His vessels are made of silver or gold, not humble clay.

From shards found above and below the grave, however, Dr. Davis

believes it was dug in the period known as Late Helladic II, a

pottery-related chronology that corresponds to 1600 B.C. to 1400 B.C.,

in the view of some authorities, or 1550 B.C. to 1420 B.C., in the view

of others.

If

the earliest European civilization is that of Crete, the first on the

European mainland is the Mycenaean culture to which the griffin warrior

belongs. It is not entirely clear why civilization began on Crete, but

the island’s population size and favorable position for sea trade

between Egypt and Greece may have been factors. “Crete is ideally

situated between mainland Greece and the east, and it had enough of a

population to resist raids,” said Malcolm H. Wiener, an investment

manager and expert on Aegean prehistory.

The

Minoan culture on Crete exerted a strong influence on the people of

southern Greece. Copying and adapting Minoan technologies, they

developed the palace cultures such as those of Pylos and Mycene. But as

the Mycenaeans grew in strength and confidence, they were eventually

able to invade the land of their tutors. Notably, they then adapted

Linear A, the script in which the Cretans wrote their own language, into

Linear B, a script for writing Greek.

Linear

B tablets, were preserved in the fiery destruction of palaces when the

soft clay on which they were written was baked into permanent form,

Caches of tablets have been found in Knossos, the main palace of Crete,

and in Pylos and other mainland palaces. Linear B, a script in which

each symbol stands for a syllable, was later succeeded by the familiar

Greek alphabet in which each symbol represents a single vowel or

consonant.

The

griffin warrior, whose grave objects are culturally Minoan but whose

place of burial is Mycenaean, lies at the center of this cultural

transfer. The palace of Pylos had yet to arise, and he could have been

part of the cultural transition that made it possible. The transfer was

not entirely peaceful: At some point, the Mycenaeans invaded Crete, and

in 1450 B.C., the palace of Knossos was burned, perhaps by Mycenaeans.

It is not yet clear whether the objects in the griffin warrior’s tomb

were significant in his own culture or just plunder.

“I

think these objects were not just loot but had a meaning already for

the guy buried in this grave,” Dr. Davis said. “This is the critical

period when religious ideas were being transferred from Crete to the

mainland.”

The

Mycenaeans used the Minoan sacred symbol of bull’s horns on their

buildings and frescoes, and their religious practices seem to have been a

mix of Minoan concepts with those of mainland Greece.

Archaeologists

are looking forward to studying a major unlooted tomb with modern

techniques like DNA analysis, which may shed light on the warrior’s

origin. DNA, if extractable from the warrior’s teeth, may tell where in

Greece he was born. Suitable plant material, if found in the tomb, could

yield a radiocarbon date for the burial.

This

and other techniques allow far more information to be extracted from a

rich grave site than was possible with the picks and shovels used by

earlier excavators. “We’ve come a long way from Heinrich Schliemann,”

said Mr. Wiener, referring to the efforts of the 19th-century German

businessman who excavated Troy and Mycene to support his view that the

events described by Homer were based on historical fact.

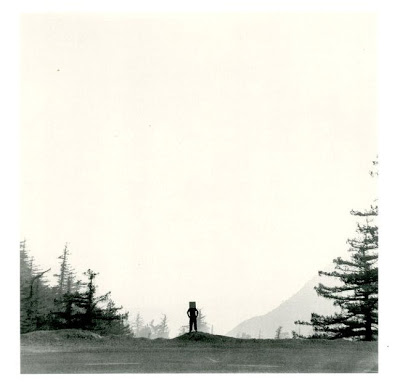

His work is hard to watch; its not music video stuff. Everything he did was totally silent. But that only enhanced the hypnotic trance the visuals lulled you into. Not everything he did was as pleasant as Moth Light or Commingled Containers. The Act of Seeing With One's Own Eyes is STILL unwatchable for most people (the title is the literal translation of "autopsy"...you can figure out the rest).

All told, Brakhage made about 400 films in his lifetime. 400! That's remarkable! Its more than the handmade craft of his work; its the raw curiosity he had about what it's like to be alive. The curiosity is priceless--you can't teach it, but you can foster it. In Brackhage's work, there's no pretense. No fashion. No grandiose proclamations. Just sheer, confrontational beauty.

What do we need to get back? We need to get back the joy of creating, of wondering. And we need to ditch the desire for fame and recognition that so often characterizes much of the "art" world.